I know what you’re thinking, ‘why would I want to find face mites?’ but the real question is, ‘why wouldn’t you’? These microscopic arachnids in the Demodex genus live in your pores eating facial oils called sebum, completely undetected by their human hosts. Unless we look for them, that is.

We’re not born with face mites, but it’s believed they are passed down to children during those intimate moments when parents embrace their children. During the day face mites rest snug inside your hair follicles down inside your pores and only come out at night. While you are sleeping the mites crawl out of their homes to crawl across your face and…mate. Then they return to their home where the females lay eggs.

They only live for about two weeks, during which time they never expel their waste because they have no anus. It builds up inside their body and when they die their body dries out and the waste deteriorates.

Humans have lived with face mites for a very long time, but despite this, we still know very little about them. They are possibly our oldest companion, older than dogs or cats.

“We still have this very ancient and intimate relationship, and it seems clear that we’ve had these face mite species with us for all of our history. So they are as old as our species, as old as Homo sapiens.”

Michelle Trautwein, Meet the Mites that Live on Your Face, NPR

We’re not the only mammal to have face mite companions, they have been found on many other mammals as well, including the duck-billed platypus. Different mammals have their own species of face mites, but humans have not one, but two different species of face mites, and they aren’t even closely related. They come in two varieties, Demodex folliculorum is long and thin and lives near the surface and Demodex brevis is short and squat and prefers to live deeper.

They can be hard to find and most methods may come up empty, but it’s believed that everyone has mites. Some scientists have discovered that by scraping a person’s face, even if they don’t find actual mites, they can find mite DNA, proving that the mites are indeed there. During one study they found mite DNA on every person they tested.

Learn more about your facial companions by searching for them. Here is how.

TOOLS

MICROSCOPE: Because face mites are so small you will need a microscope to look for them. A simple compound microscope will be suitable.

SLIDES: You’ll need basic microscope glass slides to view the face mites.

TAPE: The tape method uses basic cellophane tape. Clear tape works better for viewing under the microscope, but nonclear types work fine. Packing tape can be experimented with and even pore strips can be tried.

CLEAR NAIL POLISH: The polish method uses a basic clear nail polish top coat.

SUPER GLUE: The super glue method uses basic super glue, but see the note under the method on the type of super glue to try.

STEPS

There are three methods you can try, depending on your materials and bravery. The first uses tape, the second uses nail polish and the third is for the most adventurous using super glue.

TAPE METHOD

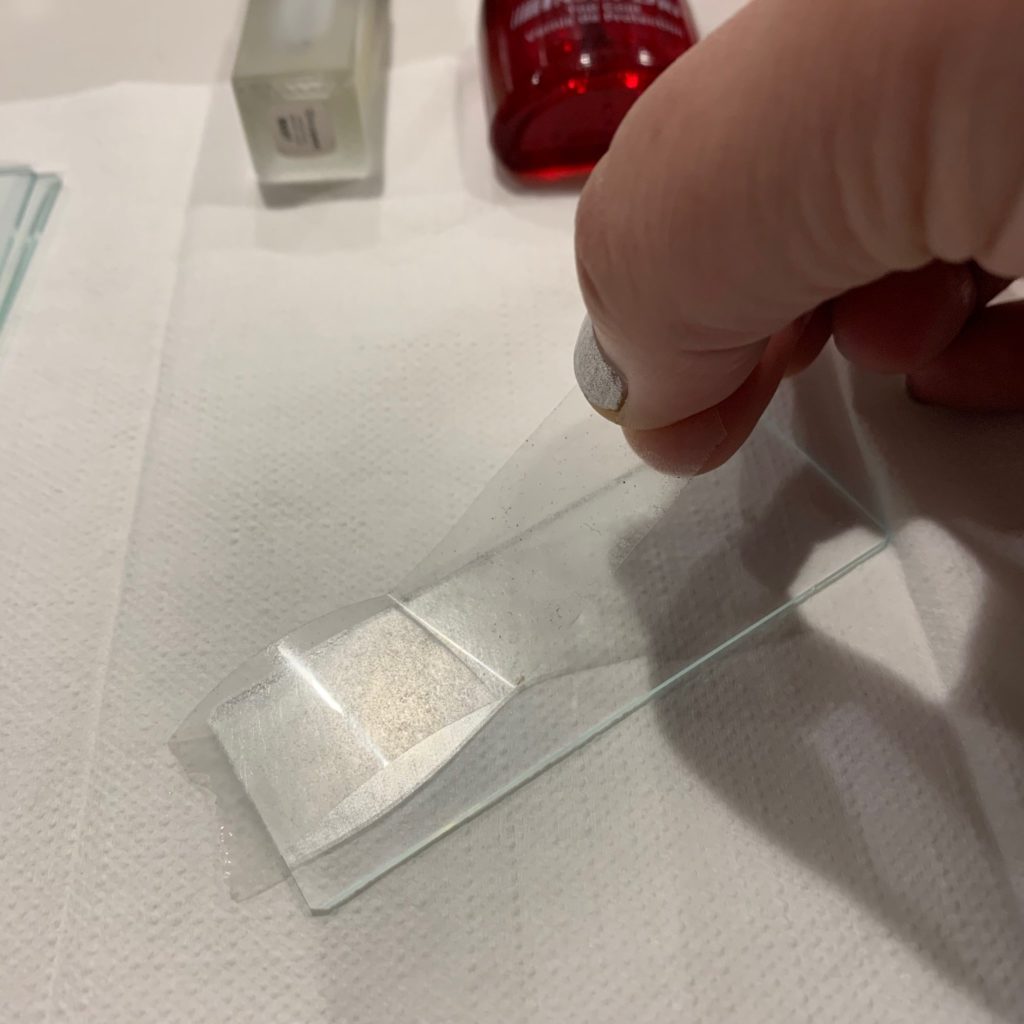

- Place tape on your face before bed. The best places are on your forehead, cheeks or across the bridge of your nose. Leave the tape on your face overnight.

- You can also do daytime tape for a shorter period of time leaving it on for about 10 minutes.

- Remove tape. Peel the tape from your face and place it on an empty microscope slide.

- View. Place the slide glass side up on your microscope and look. The mites will be found at the end of the hair follicles. Use between 40x and 100x magnification.

*Note: face mites desiccate quickly once removed from the face, within about five minutes, so look at the slide immediately.

NAIL POLISH METHOD

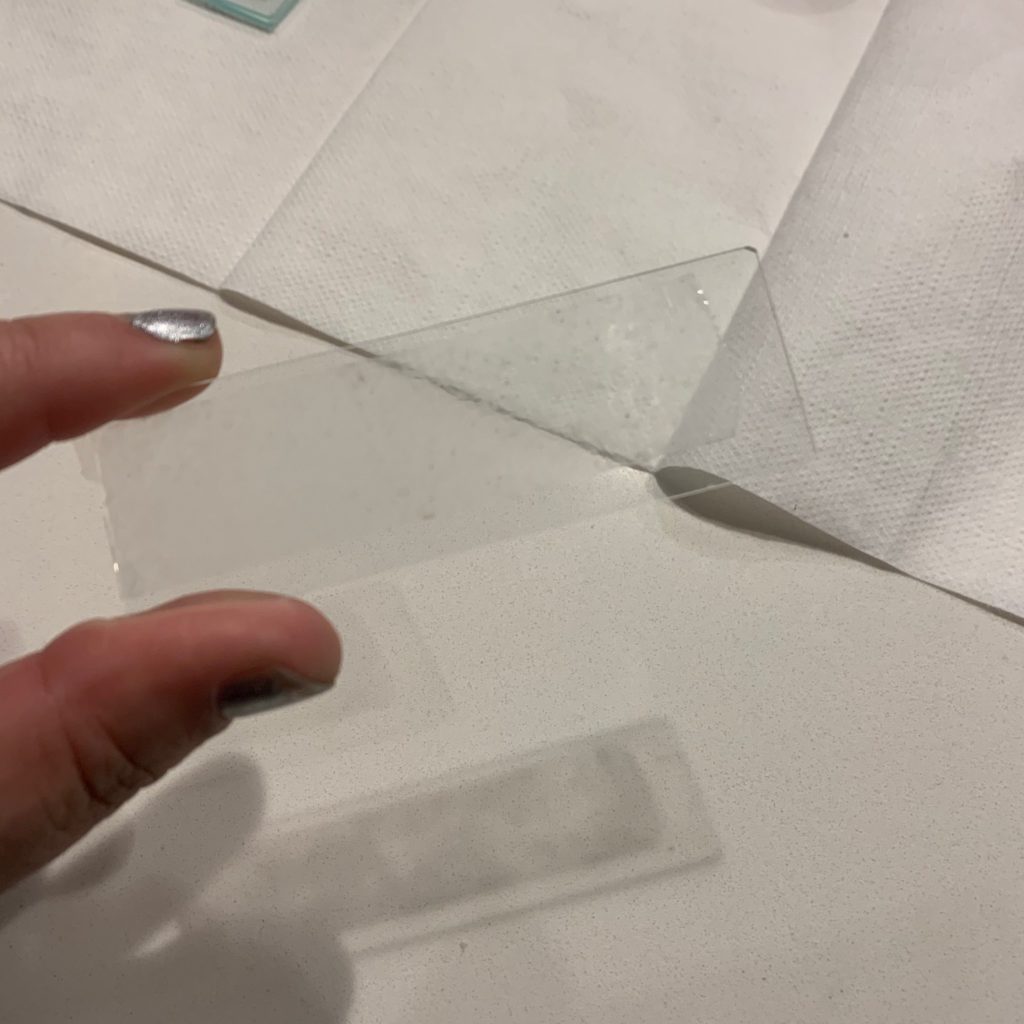

- Put a very thin layer of nail polish in the middle of the slide.

- Let it air dry for about 60 seconds.

- Place on your face (forehead, cheek, nose) for about 30 seconds. Be cautious using under your eyes because the fumes may irritate them.

- Remove the slide from your face and place a slip cover over the top.

- Place under the microscope and look!

*This ingenuous method was developed by Mo Kaze and is much more gentle than the super glue method that follows.

SUPER GLUE METHOD

*WARNING* Use this method at your own risk! Studies show this shouldn’t damage skin, but use extreme caution. If applied close to the eyes, the fumes can irritate the eyes.

- Spread a thin layer of glue onto a glass microscope slide. Too thick and you’ll leave behind the glue on your face instead of the slide.

- Immediately place the slide, glue side down on your face. The best areas are the forehead or cheek.

- Leave the slide in place for a few seconds.

- Gently peel the slide off your face.

- View under the microscope starting with 40x magnification moving up to 100x. With this method the mites will be at the end of the follicles, furthest away from the skin on the slide, so you want to focus on the tips higher up.

*Note: not all super glues are created equal and some may not bond with the glass, while others may obscure vision on the slide. In the study on Demodex linked to under ‘Resources’ below, the glue they settled on was a standard super glue from Loctite. I had luck with Gorilla super glue which comes with a built-in brush.

FACE MITE STORIES

Several people on Twitter have experimented with finding face mites and here are a few of their stories.

Battle anthem for #TeamFaceMite! Enter the Sandman by Metallica 🤘

— Marianne Denton (@Astro_Limno) February 28, 2020

“It’s just the beast under your bed

In your closet, in your HEAD”#MMM2020 #TeamInvert pic.twitter.com/P6SnBVGtHc

Setting up my #facemite experiment! 🤞🤞🤞@MaureenBug !!! pic.twitter.com/qHY0yc1cZf

— Mo Kaze, Protein Voltron 🤖 (@MoKrobial) March 1, 2020

Thank you to Twitter friends Marianne Denton, Maureen Berg, Mo Kaze and Michelle Trautwein for all of their help and expertise!

Resources:

- Meet The Mites That Live On Your Face: NPR

- ‘Face Mites’ Live in Your Pores, Eat Your Grease and Mate on Your Face While You Sleep: Live Science

- 3 Things You Didn’t Know About the Mites That Live On Your Face: Discover Magazine

- These Microscopic Mites Live on Your Face: BBC Earth

- Good News: We’ve All Got Mites: Your Wild Life

- Ubiquity and Diversity of Human-Associated Demodex Mites

- Study of Demodex mites: Challenges and Solutions

- Methods for extraction and ex-vivo experimentation with the most complex human commensal, Demodex spp.

Here’s a discussion on Twitter with a scientist who studies face mites:

Hi @flylogeny! Just saw your NPR video on face mites! Can @MaureenBug and I ask you some questions?

— Mo Kaze, Protein Voltron 🤖 (@MoKrobial) February 28, 2020

Your illustration of Demodex is excellent! The article was enjoyable and informative. Do you have any interest in doing more in this area?

Best Regards,

Joe Vehige

I cannot sleep and for the last hour or so I have researched face mites lol. I have no glue or microscope but tried it with tape. Residue was found on the tape but it may have just been the oils in my skin. I was hoping to see movement. I need to order a microscope now just to find my mites!

Do you have any photos of them AND a hair follicle to get an idea for size? I am a biology teacher, and want to try this with my students.

Hi Matt,

I’m happy to hear you want to introduce your students to face mites! You can find a good photo of the mite and follicle in this article about face mites from NPR: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/05/21/725087824/meet-the-mites-that-live-on-your-face