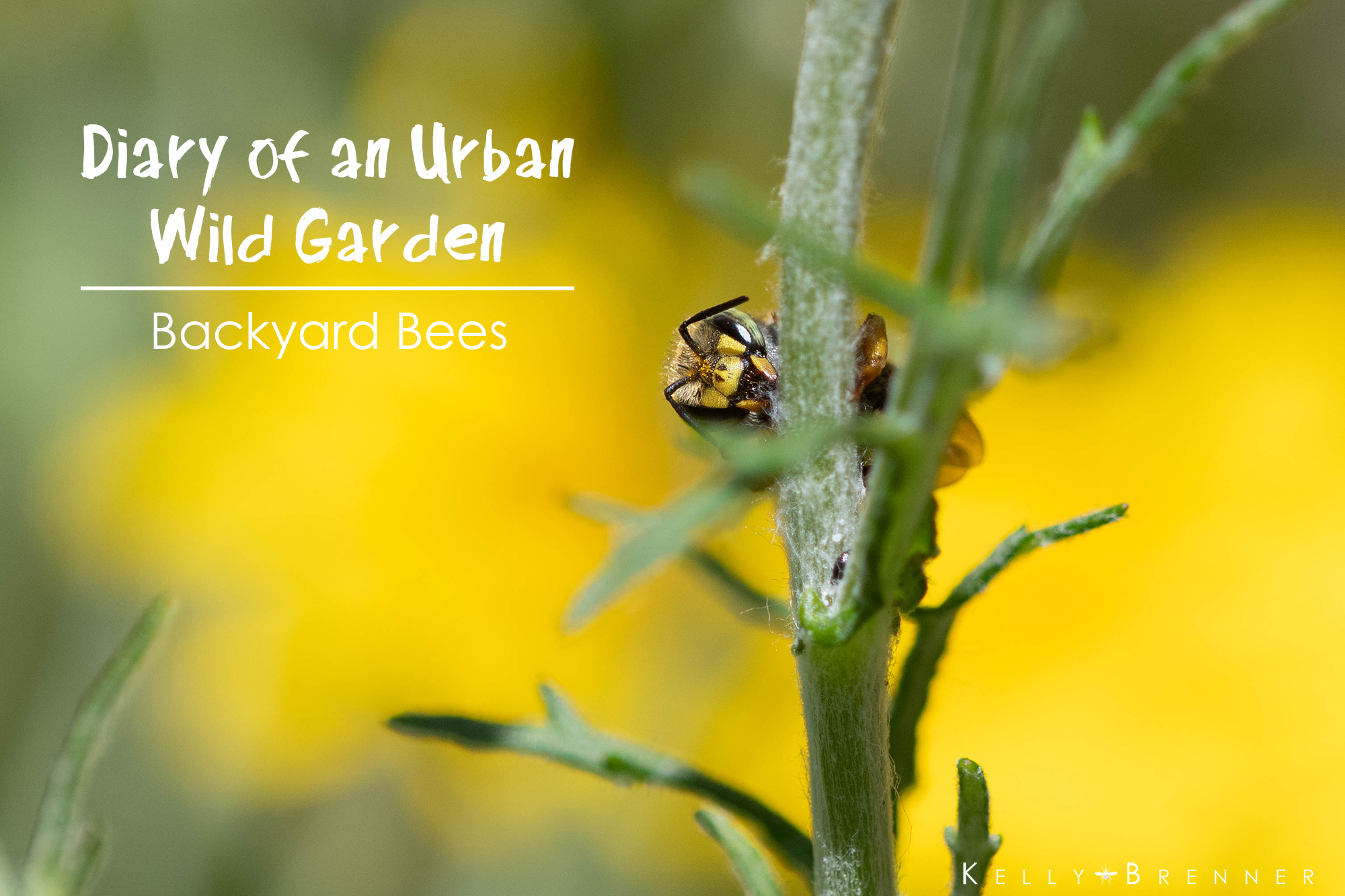

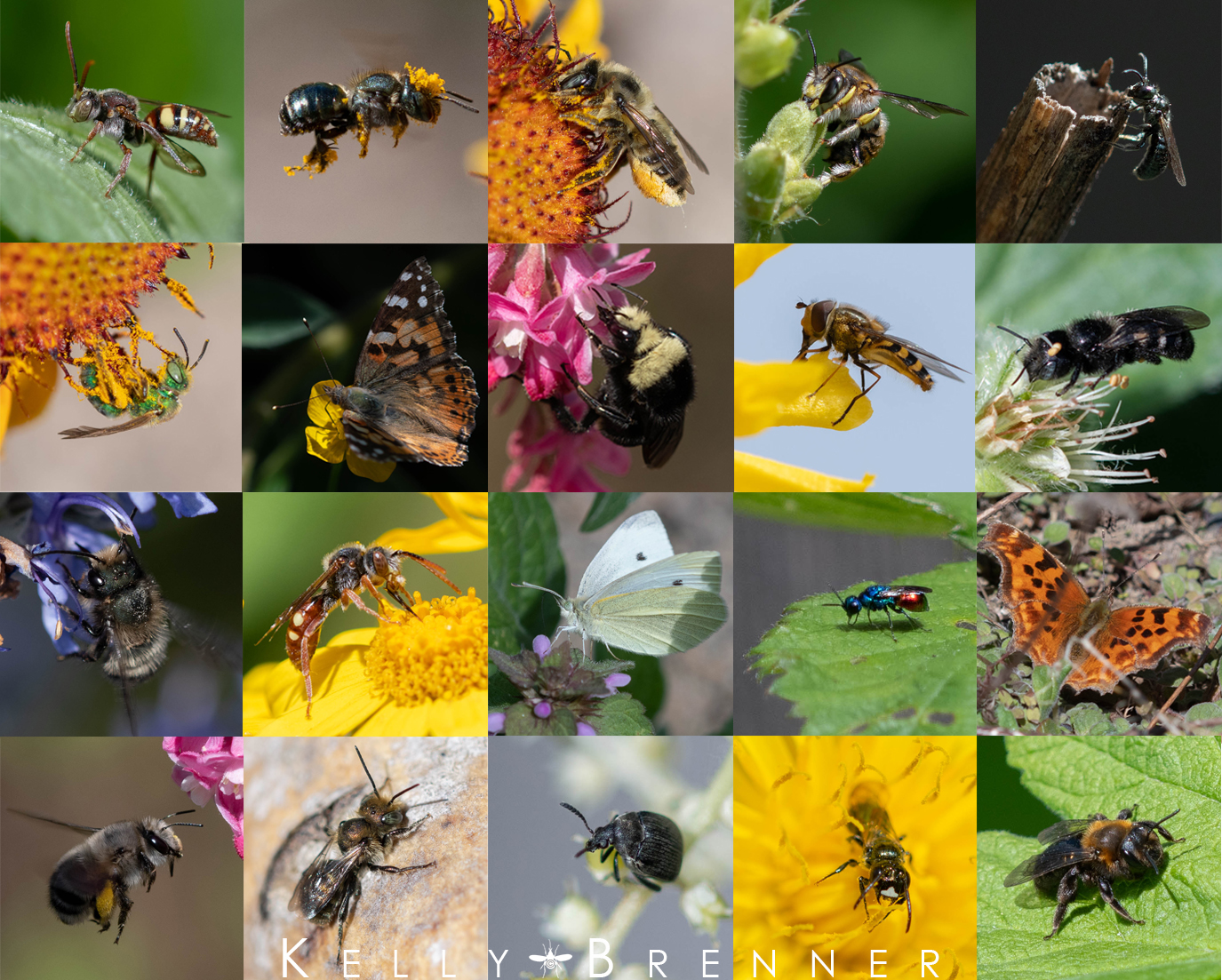

On the door of my study hangs a poster of the backyard bees of North America and often when I’m thinking, my eyes fall on this poster and I lose my train of thought as I examine the multitude of bees. My thoughts turn to the many bees I’ve watched in my wildlife garden and how each year, more and more show up as the plants mature and I add new native flowers.

Butterflies, moths, beetles – they come and go and I can’t be guaranteed seeing them on any given day, but bees, they are always there and I can go out anytime from spring to autumn and know I will find them. My yard isn’t large, but I’ve followed the advice of the Xerces Society’s book Attracting Native Pollinators and planted a variety of native flowers, avoid pesticides and offer nesting locations, so the bees come in numbers.

I’m still learning to tell the different bee families apart, but over the last couple of years, with the help of The Bees in Your Backyard and help from experts on Twitter, I’ve gotten to know a few of them. Here are a few of the bees that visit my wildlife garden.

Leaf-cutter Bee (Megachile)

I knew I had leaf-cutter bees in my yard long before I saw one because I noticed circular holes in the leaves of my vine maple trees, almost like someone had taken a hole punch to the edges. Female leaf-cutter bees use their jaws to cut along leaves or flowers, creating the hole on the edge of the plants. They take the material back to their nest, which is a hole in a place like a plant stem or in decomposing wood, and uses the leaf or flower petal to create a sort of wallpaper in the nest. She’ll lay an egg, leave some pollen and close up the cell with more plant material. Some species are quite particular about the type of material they use for their nests, some like certain flowers, others like specific leaves. I have not yet caught a leaf-cutter actually cutting my leaves, but this year I finally saw the bees foraging in my yard.

These bees are easy to distinguish from other bees because they collect their pollen on the underside of their abdomen, not in pollen baskets on their legs like most other bees. As a result, when they are on the flower, their abdomens are very active moving up and down and the underside is often bright yellow, where the pollen has been gathered. Some species of leaf-cutter bees are also picky about their food source and visit only a certain genus or prefer a species, but most are generalists. The leaf-cutter bees in my yard seem to prefer the blanketflower, which is a reliable place to always find one. I know if I sit down next to the flower, within a minute or two a leaf-cutter bee will show up.

Digger Bee (Anthophorini)

Some bees are easy to overlook, but not the digger bees. They are large, fuzzy and loud. This last summer I found them constantly around my red-flowering currant and without looking I knew they were around because of their frantic, loud buzzing. These are one of the earliest bees of the year, showing up in the early spring. Like bumble bees, digger bees are active when most other bees aren’t. When the temperatures are low they are flying around because they shiver to warm up so they can be active. But there’s a downside, they can get too hot during the middle of the day and have to retreat to the shade of their burrows.

As their name indicates, they dig burrows to make their nests in the ground.These hairy bees are very good at carrying pollen so they are beneficial for native flowering plants as well as crop species and they are mostly generalists so will visit a wide variety of plants.

Cuckoo Bee (Nomada)

Some bees go about their business of pollinating, mating, making nests and laying eggs. And then there are cuckoo bees. I confess, these are one of my favorite bees I encounter in my wildlife garden as they forage for nectar. They are striking with red and yellow stripes and they have a complicated relationship with other bees.

The name ‘cuckoo bee’ refers not to a family of bees, but a lifestyle. Cuckoo bees are found in different genus, the ones I am most familiar with are those of Nomada which are found in the Apidae family of bees. These cuckoo bees are cleptoparasites, they lay eggs in the nests of other bees, usually on the wall. Once the first egg of the cuckoo bee hatches, it uses its large mandibles to attack the other eggs – both host bee and siblings alike, or if eggs have already hatched, the larvae. The single victorious larva then consumes the pollen that was gathered by the host bee at their leisure.

Each species of Nomada bee parasitizes only one kind of other bee and for some reason, cuckoo bees often target closely related species.

Green Sweat Bee (Agapostemon)

These metallic, green bees may be the most striking bees I see in my wildlife garden and they’ve been regular visitors since I began transforming the yard with the first flowers. They are unmistakable, shiny and green. Male bees have a striped abdomen, the ones I see are black and white striped, while the female bees are usually entirely metallic green. Another name for these are metallic green bees.

They feed on most anything and I find them on many different flowers in my yard. These sweat bees nest in the ground and I leave areas of bare soil in sunny locations for them and other ground nesting bees.

Wool Carder Bee (Anthidium)

These bees are aptly named because I can sit down next to my woolly sunflower plant and watch female wool carder bees visit. Once they land, they begin using their mandibles to scrape the fuzzy fibers from the stem and gathering it into a ball underneath their body. Once she has enough, off she flies to use it for her nest where she lines the cells with the ‘wool’.

The male, on the other hand, is significantly larger and is busy patrolling a patch of Cooley’s hedge nettle on the other side of the garden. The species I have seen in my wildlife garden are an introduced European bee, Anthidium manicatum and although I haven’t seen it, males of this species are known to attack any other bee in their territory, sometimes so violently they can knock the other bee right out of the air. The male wool carder does not have a stinger, but he does have small spines on his backside which is a sure identifier of this species.

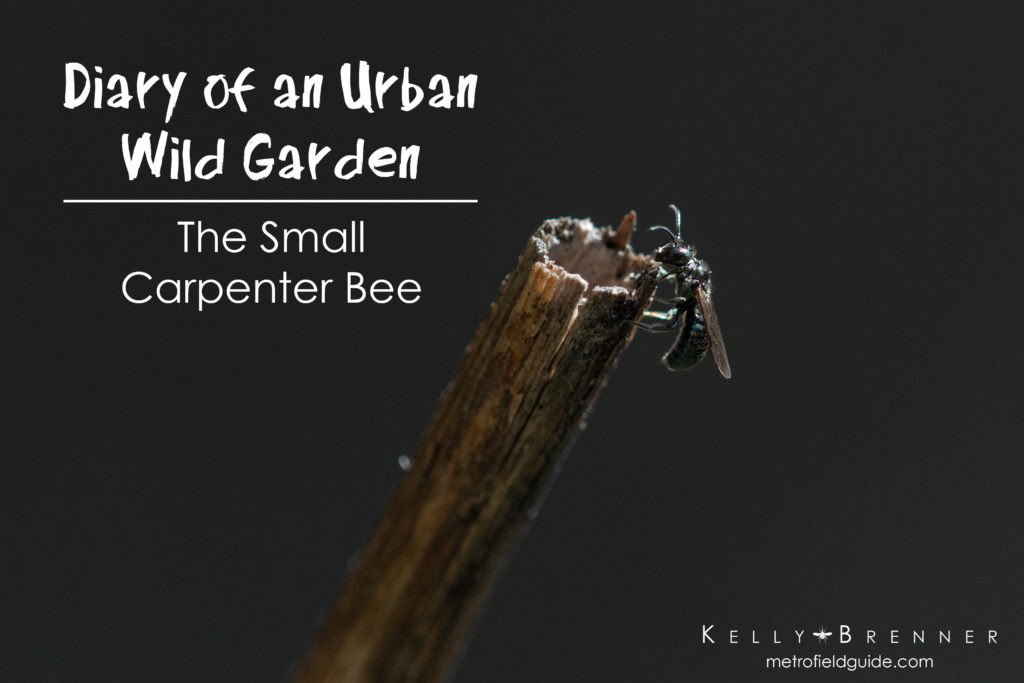

Small Carpenter Bee

I’ve already written about the small carpenter bees in another Diary of an Urban Wild Garden entry when I watched them mate and lay eggs in the hollow aster stems in my yard.

Great article! I’ve been wanting to get one of those stick houses that serve as odd bee nesting sites. Neat to know how many different native bees are out there.

The only one of these i know I have seen are sweat bees, which land on your arm while fishing to drink your sweat. If you swat them, you get a sting!