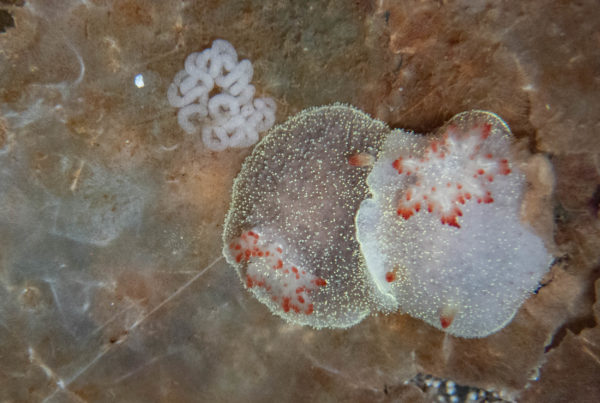

Nudibranchs are weird. They claim to be slugs but their variety of shapes and colors defies the very definition of what a slug looks like. And yet, even among nudibranchs there are some species that raise the bar on weird. Enter the Melibe genus of nudibranchs. Their very existence is hard to comprehend. At their core they have the basic slug body. And that’s all that’s basic about them. The species we have here in the Pacific Northwest is Melibe leonina and their bodies are nearly transparent. They are a frosted white, but you can easily see all of their internal organs. And they are coated in white spots which makes them rather look like they are carrying around constellations. And that’s not the end of their uniqueness. Although they move slowly along the seaweed, they can also swim quite well by flexing their body back and forth. Very few nudibranchs can actively swim.

While many nudibranchs have finger like cerata on their backs, Melibe go a step beyond and have flattened, paddle-like cerata. They are large, nearly as large as their head and there are between four and six pairs on their back. They flap around like sails in the water as the nudibranch slowly moves along seaweed. If the cerata is backlit, you can easily see what look like veins branching through each one, but they are in fact extensions of the nudibranch’s gut.

So far so weird, but we haven’t talked about Melibe’s head yet. Unlike other nudibranchs, they have no radula (the scraping teeth common to most slugs and snails). Instead, they have an overly large oral veil. Their head is basically a giant hood. It opens in the front vertically to their body and is lined with small tentacles. They open their hood, sweep it back and forth in the water and then close it again, trapping small invertebrates inside with the tentacles acting like a cage. They eat their prey, which includes copepods, amphipods and other small zooplankton, whole.

On top of these strange heads sits their rhinophores, which as is befitting of this species, are also unlike that of other nudibranchs. Instead of the usual range of shapes, this species has flattened rhinophores that look more like ears. They’re in theme with the paddle shaped cerata and round head, so perhaps they’re appropriate for this wonderfully strange nudibranch.

I had long wanted to find one of these unique nudibranchs but hadn’t had any luck. I’d even gone to San Juan Island looking for them because there were numerous records of observations in Friday Harbor, but had failed to find any. So when I heard from someone first hand who had seen them (at the same time I had been in Friday Harbor on my futile search) somewhere much closer to home, I couldn’t resist a trip after I’d returned. My intel was good and I quickly found my first Melibe, more commonly known as the Hooded or Lion’s Mane Nudibranch in a harbor hanging out on seaweed on the side of the dock.

Seeing it for the first time in real life was surreal. Some creatures, like tardigrades for example, are just so bizarre that nothing can prepare you for actually setting eyes on them in person. It’s hard to believe such a strange animal is real. Especially when they start moving. It’s one thing to see a photo, but something entirely different to see it moving and being pushed around by the waves. Even in a relatively calm marina, the water movement is significant for a creature only a couple of inches long.

During my outing I found not only one, but a half dozen different Melibe and it was everything I could have ever wished for. And then some.