While many species may come to mind with the term ‘urban wildlife’, otters are not likely among the first to come to mind. Despite this, they can be seen in urban areas. In fact in three of the last cities I’ve called home, I’ve seen River Otters in two of them.

River Otters can be found throughout most of North America in fresh and even salt water. While River Otters may be common throughout the region, they are less common in urban areas. When I saw a River Otter in Eugene, Oregon along the Millrace which runs through town, nobody believed me until I shared the photos to prove it wasn’t one of the abundant nutria. It wasn’t the last time I saw that otter during the three years we lived there either. However, they are most common in waterways and watersheds which contain clean water with healthy fish populations. You can find them in estuaries, creeks, streams and rivers, lakes and wetlands. They are also found in coastal marine habitats, which is why many people think they have seen a Sea Otter.

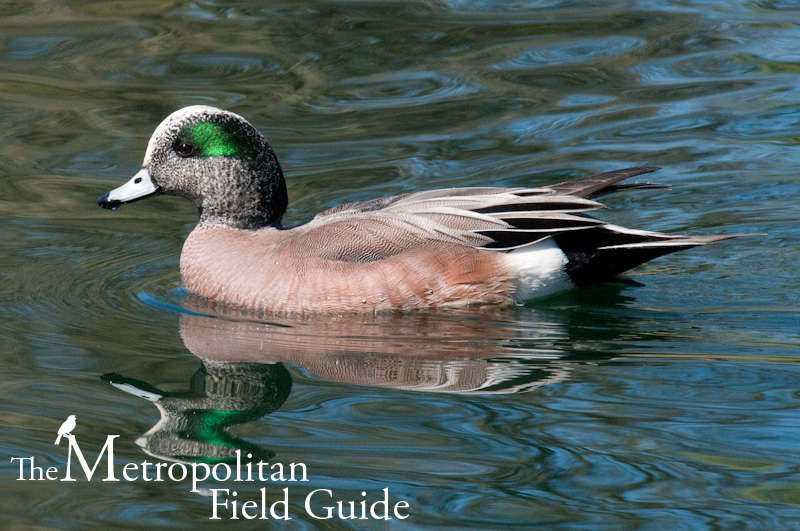

River Otters (Lutra canadensis) are not to be confused with the similar Sea Otter, or other common urban aquatic mammals such as nutria. River Otters are about 4′ long while Sea Otters are closer to 6′ and rarely come to shore. River Otters have brown fur which covers a long, narrow body with short legs and a tail with a tapered end which is also covered in fur. They have a dense cluster of whiskers which are sensitive to movement and aid in their hunting in murky waters. Their toes are webbed and their nose and ears shut when the otter dives under water where they can stay submerged for up to 8 minutes.

Otters are fairly easy to differentiate from Nutria with a little observation. Nutria do not have any fur on their tails. Nutria also swim differently than otters with a straight, ‘dog-paddle’ style as opposed to otters which weave, dive and are generally more agile.

River Otters are almost entirely aquatic, but unlike the Sea Otter, their dens are on land and they can be found foraging along shores and banks. They can be seen during both day and night, although are reported to adopt a more nocturnal nature in urban areas. They do not hibernate and can be seen during all seasons. Some signs of otters along a river or stream are paw prints and also slides which are little trails of mud or flattened plants.

Their dens are used for not only giving birth but also for sheltering from bad weather. They make their dens in a wide variety of places including hollow logs, piles of debris including wood and rocks, log jams, vacated dens of nutria or beavers or even human made shelters such as decks. Dens are lined with a variety of soft materials including vegetation, fur and moss. They are very hard to find with entrances far below the water line which helps protect from predators as well as ice. Dens can be found along water or as far as half a mile away from water.

Otter mothers give birth every other year from March to May to anywhere from 1-5 pups. Interestingly, the River Otter has what is called delayed implantation. Their gestation period is 9-12 months long because the fetus does not immediately implant in the uterus, instead waiting a time. Comparatively, otters from Europe have a gestation of only two months. Young otters grow up quickly; within a month the pups are playing, by seven weeks they are swimming around and in the fall they are off to establish their own territories. If you see an otter far from water during this time, it is likely a young one looking for a place of their own. They hold large territories and have been known to travel as many as 150 miles in a year often moving 25 miles in a single season.

There are many species of marine mammals and birds which attract the ire of fishermen, however the River Otter has been documented to feed mainly on non-game fish. Not only do they not eat a large amount of game fish, they are known to eat a lot of so called ‘trash fish’, species which compete with the fish we prefer. Their sense of smell is excellent as they can detect large congregations of fish from far downstream. While their main staple is fish, they eat a wide variety of food including amphibians, bird eggs, crayfish, clams, birds and even small mammals. They are skilled hunters and can take a bird from underneath, dig turtles out of the muck and even prey on snapping turtles. In turn they are prey, particularly when on land, for larger mammals including coyotes, wolves, bobcats and even Great Horned Owls. As an unprotected species, they are also still trapped for their fur and being at the top of the aquatic food-chain, they are particularly susceptible to contaminants including pesticides, mercury, PCB’s and other pollutants. Wild otters typically live up to 9 years but in captivity they have been known to live to a ripe old age of 21.

Perhaps one of the most endearing traits of otters is their playful behavior. While many mammals play when young, otters never stop playing and can be found in playful behavior throughout their lives. Otters have been observed sliding down snow or mud banks and burrowing through snow. They are also full of curiosity and will investigate things which are new or different. However, they will fiercely defend themselves, especially when they have young.

Otters have become a less rare urban species and have made appearances in cities in North America and Europe including Cork City, Ireland, many British cities, Boulder and San Francisco. In the U.K. the return of the otters is attributed to cleaner urban waterways which increases the local fish populations in the cities. This is good news there as the otters compete with the invasive mink, a species responsible for predating on the native water voles, which have been suffering from a critical decline in numbers. Otters are a good indication that local waterways are getting cleaner so hopefully we’ll see a lot more of them in cities in the future.

There is a cornucopia of papers and information about otters at the River Otter Alliance page.

The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife have good information about River Otters including how to deal with any human conflict on their Living with Wildlife page.