Every night from fall to spring, upwards of 10,000 crows fly from downtown Seattle and other surrounding areas to the University of Washington’s Bothell campus, located on the far north end of Lake Washington. They are here for their nightly roost, where all 10,000 of them, cawing and making a ruckus impossible to miss, gather together before descending into the wetland trees. There are several other crow roosts around the Puget Sound area, but none as large or magnificent as the Bothell roost.

Along with the University of Washington, Cascade Community College shares this campus and hosted a crow evening this past fall which included Audubon representatives on hand with bird information, crow hats for the kids, cider for all and a talk by crow expert Kaeli Swift.

I confess I’m a bit crow mad, as long-time readers may have gathered from past posts, Emerald City Crows, A Murder of Crows Friday Film and book review of Crow Planet. I increased my crow interest when over a year ago when we moved to south Seattle, and I immediately noticed a crow movement every evening to the south. Nightly I’d watch the river of crows flowing over our house, commuting to their evening roost and wondered where they went. On more than one occasion I wanted to follow them by car. I have since discovered where these crows head nightly, quite by accident, and while their gathering is fun to watch, it’s nowhere near the size of Bothell. So when I heard about the large roost in Bothell, I had to see it.

The Main Event

Although I attended the crow event in the fall and saw a small part of the spectacle, it wasn’t until I went back in January and witnessed the full show that I truly appreciated this magnificent display. After arriving early, I worried at first that they had decided to go somewhere else for the night because I saw not a single crow, for what seemed, a long time. Finally, a slow trickle started to arrive from the south, but they went right past the wetlands and again I worried that they weren’t coming. For a while I watched them slowly pass by, seeing much what I was used to seeing from my own house.

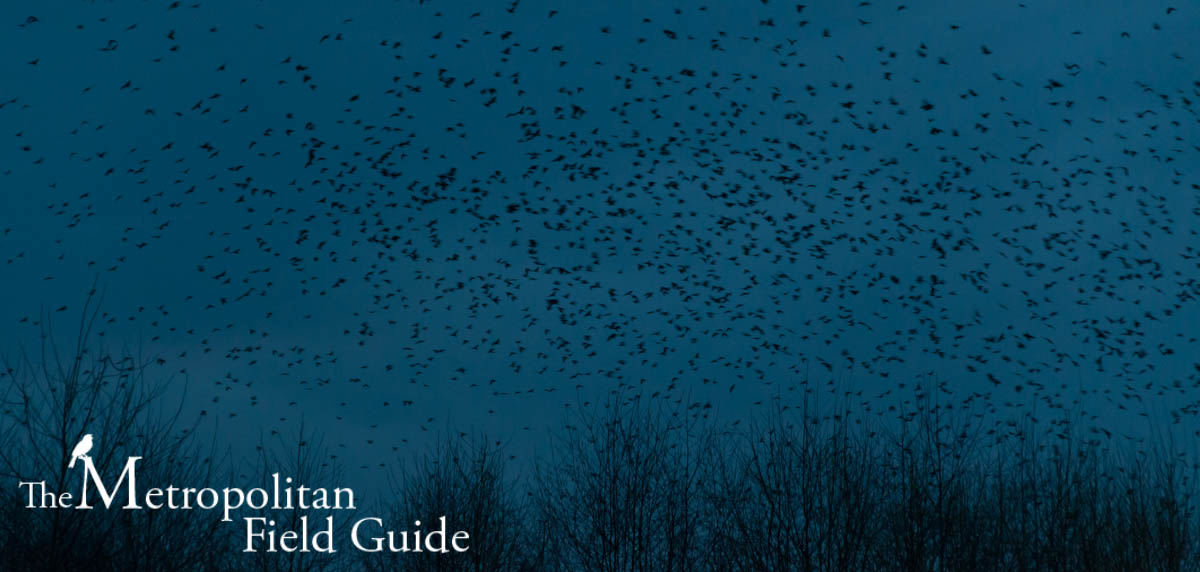

And then suddenly they started to arrive. At first a small stream from one direction, and then more and more from several directions. Pretty soon the small streams become wide rivers, flowing in from several directions and eventually the sky was covered in evenly spaced crows. Instead of heading straight for the trees in the wetlands, they headed for the tall Douglas Fir trees on the hill by the campus buildings. There they circled, mingled and many landed, unseen in the branches of the trees. Soon, as the trees filled up, more landed on the roof and others in the bare branches of the deciduous trees. Their numbers quite hidden among the trees and buildings with more and more still flying in.

Before they even finished arriving in that location, they began swooping over the fields down into the wetland trees. Although it’s very noisy and chaotic, there’s a sense of order to this operation. They don’t all move at once, and they start landing in the trees at the south end first. The sky is a solid mass of crows as they continue flying down the hill into the trees. As I stood under them I kept turning in circles, watching the late-comers still arriving from the north, turning to watch them fly down from the hill, turning again to watch them land in the trees.

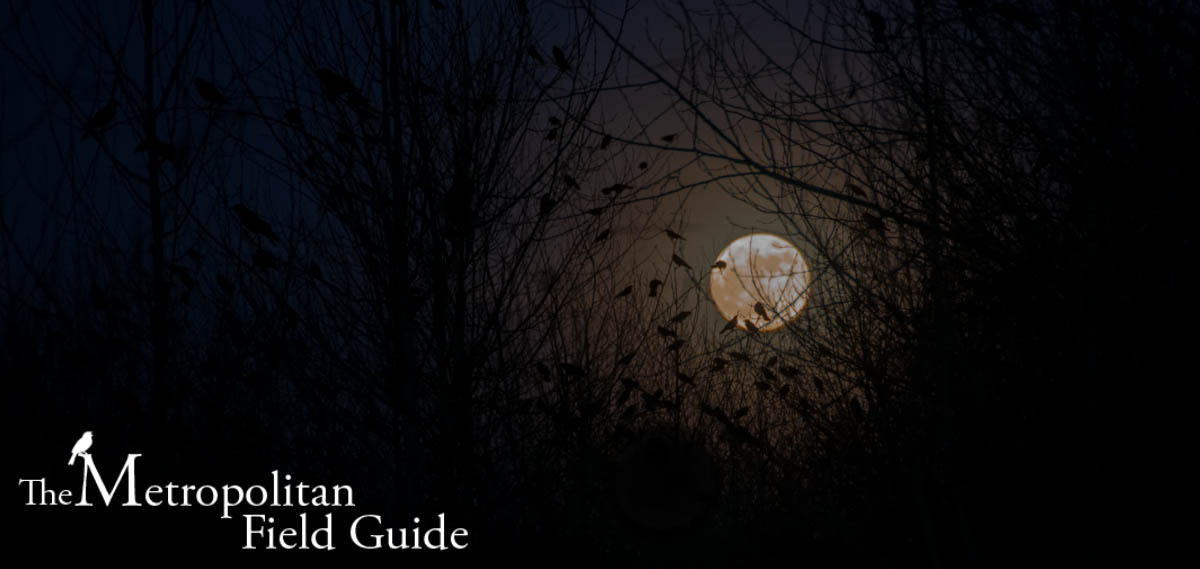

The crow’s flight is very even, not at all like the Starling murmurations which create such amazing art in European skies, or the Vaux’s Swifts which gather and swirl into chimneys. They space out, not too close together, yet not too far apart either. It’s very orderly, a steady mass. As they gather in the wetlands, I turned and walked down the short boardwalk into the middle of the trees. Where order reigned outside, it seemed complete chaos inside. The crows shifted about, cawing and making a noisy ruckus. It seems like they’ll never settle down as something unseen causes them to give up their position and move from one tree to another. Slowly, fewer and fewer fly about and it gets a little less noisy. Then, very suddenly, as I walked out of the wetlands, it goes very quiet. The show is over.

About the Crows

Perhaps the biggest question is why do 10,000 crows meet every night at this location? What most people assume is the biggest reason is that there is safety in numbers in this enclosed, secure location. The cottonwood, alder and willow trees in which they roost act as a sort of cage. As they drop down into the branches, they are enclosed and if a predator should land at the top of that tree, they will feel the movement as it echoes down through the branches.

However, there’s some suggestion that the communication and socialization could play an even larger role. Crows are suspected of sharing information about food sources at the roosts.

Kaeli Swift is studying crow behavior at the University of Washington and tells me about this information sharing that, “In fact this has been suggested as one of the primary reasons for roosting. How they communicate the location of food is not yet known, though some studies suggest knowledgeable birds display before heading to the food site, thereby informing others of their knowledge (kind of like a bee dance but not as specific). My interpretation of things is that ignorant and knowledgeable birds team-up before the morning display (i.e roost close to each other) but I don’t know if this is by chance or not.”

Crows don’t necessarily share information only in their family groups either, as Swift explains, “This is especially true for vagrant juveniles who are really depending (especially in the case of ravens) on others to help them locate food bonanzas”.

The placement of each crow in the tree is quite a complex hierarchy. The research of “Professor John Marzluff, of the University of Washington School of Environmental and Forest Sciences, and others, has shown that social hierarchy seems to play an important role in the organization of the roost site. Senior members may occupy higher perches, while younger individuals settle in the lower areas. At night, most crows move down into the thicker branches to reduce the effects of wind and rain. Research has also shown that the young crows form circles around the elders, maybe as trade for a day of good foraging and companionship.” (4) This likely explains the chaos and shifting about I witnessed inside the roost. Each crow was trying to find the ideal perch, not too high or too low and close to specific individuals.

The crows may also use the roost as a singles mixer, scoping out potential mates for the upcoming spring. Thermoregulation is yet one more benefit of gathering in these roosts, helping keep them warm in the cold nights.

Another common question is where are they all coming from? As there are several roosts, it’s often hard to tell, but these birds tend to come from downtown Seattle all the way to the Snohomish Valley. Swift explains to me that which birds go to what roosts can have to do with what roost the bird is closest to at dusk, but this may be somewhat flexible on a day-to-day basis, particularly among the younger birds. Older birds who have territories to defend may go to the same roost more consistently than a young bird which is following different sources to food.

As the birds start to move towards the roost around dusk, they make stops where they gather before moving to the roosts, as I observed when many flew past the site of the roost early on and again when they converged in the trees on the hill above the roost. This is called staging and it’s still a mystery as to why the crows gather in these locations before moving to the roost for the night.

Seattle residents may recall a time when crows roosted at the Union Bay Natural Area, also commonly called ‘The Fill’ the site of a former landfill. These birds abandoned this roost in favor of the wetlands in Bothell for reasons not entirely clear. Swift says, “why they switched we can’t say for certain, but it’s likely that the mitigated wetland in Bothell became a more ideal habitat due to temporal changes in the vegetation structure. As you know, environments are not static and if birds find an area that is better for whatever reason it appears they can switch”.

Does this nightly chaos have any impact on the wetlands ecosystem? Swift tells me that it’s uncertain. It’s likely that such a large number of birds in one place help spread disease, but this is a “hot topic of research” so hopefully we’ll learn more about this in the future. They could also scare away nesting songbirds in the spring and summer. However, if the site monitoring is any indication, it’s still a healthy ecosystem.

The University of Washington has a rather well-known crow program headed by professor and author John Marzluff. There they maintain a crow map which shows directions crows are seen flying, their known roosts and nests.

About the Habitat

Historically, the location of this roost sat on a floodplain, part of the North Creek, which still runs through the middle of the roost. This “site consisted of a complex array of channels, small backwater lakes, and depressions that were part of the junction environment where North Creek flowed into ‘Squawk Slough’ (now the Sammamish River). The hydrologic characteristics of the UWB/CCC site were controlled by the interaction of runoff from the North Creek watershed and the natural fluctuations in water levels of Lake Washington.”(1)

During this pre-European time, the site had a complex ecosystem. However, by 1895 the site was logged and later even further degraded by the straightening and channelizing of the creek for the transportation of logs. Post logging it was used for agriculture which saw even more transformation as the farmers dealt with the wet location by constructing extensive drainage channels. (1)

As with many other locations along Lake Washington such as Magnuson Park and Pritchard Wetlands, the Ballard Locks altered the landscape by lowering the water level of the lake about 9 feet. Further modern development with all the flooding and stormwater problems we face continued to alter this site.

When the UW/CCC campus was built, the planners and the state decided not only to minimize the impact of the site, which it was required to do by law, but to restore the entire floodplain, save six acres which were filled by campus development. (2) The final approval for the restoration work was given in 1998 to not only restore 58 acres of floodplain, but to create a new primary and secondary channel.

The effort to restore nearly 60 acres amid an increasingly urban area was directed by a very thorough team consisting of L.C. Lee & Associates, Inc., an environmental consulting firm with an expertise in wetlands and rivers, Otak Inc. as the civil engineers and two fluvial geomorphologists from the University of Washington.

Lyndon C. Lee designed this restoration as a bottom up approach in which they created the best wetland system possible with the expectation that the wildlife will follow. Instead of targeting specific wildlife species, Lee targeted improving the ecosystem functions.

“A new, meandering stream channel and complex floodplain microtopography were the first things created in this project – to serve as a template for the biological communities.” (3) The stream channels were created from scratch, to mimic conditions found at reference sites in the Puget Sound. Both channels were designed with the expectation and allowance of annual flooding over the banks in an effort to reestablish the stream to the floodplains. The design of the floodplains allows for both long and short term water storage.

Fish are important to North Creek and this restoration work improves their habitat by re-establishing the complex flow patterns of the water, Lee explains. By slowing the water down and spreading it out, this creates a complex habitat.

The target goals of the stream restoration were “maximizing channel length, maximizing contact time between water and wetlands, creating secondary high flow channels, placing large wood in-channel to guide channel alignment and morphology, providing for increased peak flows as a result of urbanization of the North Creek watershed, and allowing lateral channel movement within design parameters”. (2)

“The new main channel was designed with bed and bank features, meanders, and a variety of in-channel habitats, including pools, riffles, and large wood. Secondary channels were designed to engage at different flow volumes and provide backwater habitat at lower flow levels.” (3) These features can be found in many streams in the Puget Sound area and aid in habitat for fish by creating shelter and even spawning areas.

A delicate balance had to be created because while natural streams change their course dramatically over time, this particular stream is situated between a campus and a highway with much less room for movement. Therefore woody debris used in a bank deflection log jam helps control the stream’s movement over time.

Dramatic new topography was also introduced to alter the past flat pastures into slopes while adding a richly varying landscape with mounds and the opposite which are called ‘microdepressions’. Some of the depressions and mounds were constructed with woody debris salvaged from the trees removed for the construction of the campus buildings.

Naturally occurring floodplains may look flat at first glance, but they contain subtle microtopography. This occurs naturally when the wind blows over trees leaving a hole with a rootball sticking up in the air. Holes can also be scoured when the water changes directions, and of course, beavers can impact floodplain topography dramatically.

Lee explains that these mounds and pits help link back to the river system by providing short and long term storage of not only water, but nutrients which are exchanged back into the river. This complex microtopography also provides refuge for fish who are looking for somewhere to avoid the high energy flows that come after heavy rains.

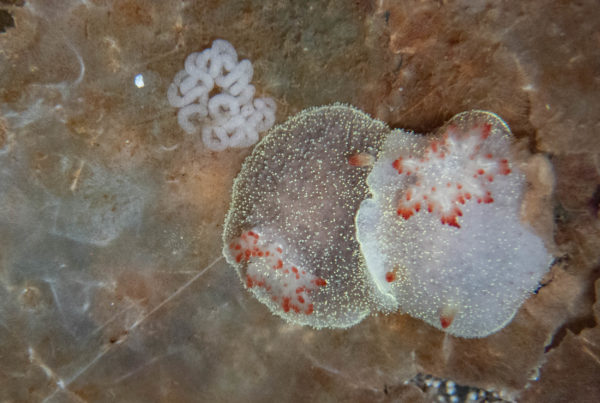

The planting of 10,000 plants was begun in 1998 but wasn’t completed until 2002. Twenty different native plant communities were introduced in the nearly 60 acres. These communities are lumped into 5 broad groups which consist of evergreen forest, floodplain and riparian forest, floodplain scrub shrub, emergent marsh and microdepressions. The plants vary from trees such as Red Alder and Douglas Fir to shrubs such as Indian Plum and Pacific Ninebark to smaller plants including several sedges.

This landscape was designed and planned with longevity in mind and many early successional species including Red Alder and Black Cottonwood were focused on with the idea that natural succession would take over and the plant communities would change over time.

The landscape was created as an emergent system, everything from the water to the wildlife to the people are unpredictable. That 10,000 crows would take over this site every night could not be foreseen.

The site has been extensively monitored including recording what wildlife has been viewed. Among the mammals are deer, coyote, beaver and raccoon. About two dozen different fish species have been seen along with two frog species two snake species and many birds in addition to crows. Visit the Wetlands Digital Collection to view photos of the many wildlife species caught on camera.

Experience 10,000 Crows Yourself

Like most other natural wonders, it’s impossible to appreciate this without experiencing it yourself, so I encourage you to make a trip to Bothell to watch the crows. You’ll want to get there a little before dusk. Simply park on the north end of campus, where there’s a handy parking garage right above the roost. Take the path that leads from the road and sidewalk, along the sports fields to the wetlands. Walk along the fields until you find the boardwalk which leads into the wetlands. This is a good place to wait. They gather at different places before they make their move to the wetlands. They have been known to land on the fields, but don’t like the lights and will avoid them if they’re turned on. When I saw them they gathered in the Douglas Fir trees and on the campus buildings before descending.

Resources

(1) Land Use History, UW Bothell

(2) Restoration Project, UW Bothell

(3) North Creek Stream Channel & Floodplain Wetlands Restoration Project (PDF)

(4) Crossing Paths Newsletter (February 2014) Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife

Great article and thank you for sharing your experience and knowledge about the crows at UWB/CC. I am a student at CC and I spend a few minutes every night… or more watching and walking around admiring the thousands of crows (I would not be suprised if it well over 10,000 now). It is a beautiful spectacle of nature and one I hope we get to see for some time.

These crows caught my attention when I worked in a Renton high rise. Every night even in wind and rain storms, the healthy crows with no eggs or hatchlings flew over our building all together. Blanketing the sky. The late ones usually had a partner. It was just amazing. I’ve also seen hundreds of them standing all over a South Center street, sidewalks, and grass not far from the river. They also seem to rest for a while beforehand, between South Center and Renton. I think they make stops like a caravan, uniting and communicating with so many neighborhood flocks as each little group joins the big group.

Hi Kelly,

I am trying to find out where Vashon Island crows roost at night. I noticed a large flocks of crows heading south above the Duwamish River last week, so I know there are other roosts around the city. Did you happy to find out where other crow roosts are located in Puget Sound are while you were researching this article? Thanks for your help. I really enjoyed your book!

Thank you, Kathryn

Hi Kathrn,

There was a map from UW that documented roosts and nightly migration movement, but it doesn’t appear to be loading at the moment. I’m not sure if it’s still being updated, but it’s here: https://depts.washington.edu/uwcrows/

I’m glad to hear you enjoyed my book, especially since I love yours!

Hi

I tried loading that but it doesn’t work.

Saw the crows at Bothell campus 2 weeks ago but will try and go tomorrow where you mentioned getting on the boardwalk to wetlands. We were above a field where the lights were on ( finally they shut them) but it certainly seemed like we were missing a better show as they seemed to be flying below us into the trees. Thanks for your article. Hope we don’t have to walk very far as a bit disabled.