In 2016 I’m doing a 365 Nature project. Learn more about the project and see all the 365 Nature posts.

It’s frequent, almost always in fact, that I’m behind on the latest books. My to-read stacks usually measure a dozen books high at any given time. But after I made an effort to start reading more diversity of nature writers, my stacks were mixed up a little. It’s partly because of this and partly because I wanted to read something everyone was talking about, which found The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World at the top of my list recently. Written by Andrea Wulf, a British writer and design historian, it quickly became a New York Times 10 Best Books of the Year and was nominated for and won a multitude of prizes.

It’s frequent, almost always in fact, that I’m behind on the latest books. My to-read stacks usually measure a dozen books high at any given time. But after I made an effort to start reading more diversity of nature writers, my stacks were mixed up a little. It’s partly because of this and partly because I wanted to read something everyone was talking about, which found The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World at the top of my list recently. Written by Andrea Wulf, a British writer and design historian, it quickly became a New York Times 10 Best Books of the Year and was nominated for and won a multitude of prizes.

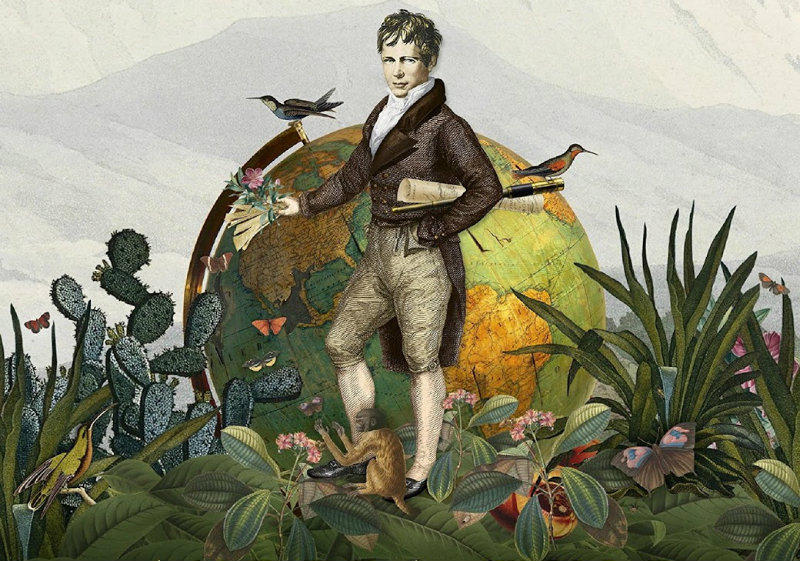

Over time, I’ve read a lot of biographies about influential naturalist such as David Douglas, William Dampier and Charles Waterton and they’re all fascinating individuals. Humboldt is no exception. Although I was vaguely familiar with his name thanks to the number of things named after him from Humboldt Penguins (which were named after the current they swim in, which is named after Humboldt), to Humboldt Bay, River, county and college – all in California. But overall, very little was remembered about the man himself. Wulf corrected this fault with an in-depth book uncovering many interesting aspects about Humboldt’s life. Despite the fact he was no great explorer and didn’t travel very much, just a couple of trips, only one to South America, he was a prolific writer and student and introduced the populace to science and nature. Not just in Europe, but across the world his books were read at the time.

He sought to rejoin the sciences which were at the time, and arguably still are, becoming quickly segregated into individual fields of study. Humboldt studied all the fields and how they were connected, eventually giving rise to the field of ecology. While he was successful in many respects, perhaps in this he didn’t quite succeed. Wulf writes, “…his more holistic approach – a scientific method that included art, history, poetry and politics alongside hard data – has fallen out of favour…As scientists crawled into their narrow areas of expertise, dividing and further subdividing, they lost Humboldt’s interdisciplinary methods and his concept of nature as a global force.” Wulf argues that at at time of climate change, this interdisciplinary approach needs to be readdressed and that’s why this book is so important.

Humboldt influenced a great many individuals who in turn made huge, sometimes monumental, impacts to our world. Charles Darwin, Ernst Haeckel, John Muir, George Perkins Marsh and Henry David Thoreau were all heavily influenced either by the man himself or his writing. He taught them how to see the larger picture, how all things are interconnected and they took the torch and ran resulting in the theory of evolution, a new art and conservation. Wulf’s book shows us Humboldt was far ahead of his time.

Wulf writes in the epilogue, “One of Humboldt’s greatest achievements has been to make science accessible and popular.” We can thank him for making nature and science writing popular.

THE INVENTION OF NATURE from Sea Blue Media on Vimeo.

Full of nature, adventure, politics and power, and family and friendships, I enjoyed this book very much.