Magnuson Park is located in Seattle along Lake Washington, north of the University of Washington. The park has a long history of dramatic land use change and part of it has now come back full circle. In the days of early settlers the area was a wetlands, alder grove, and Douglas fir forest with trees up to six feet in diameter. In the following years the site saw a homestead, brickyard, shipyard and post office. This landscape was altered in 1917 with the building of the canals and Ballard Locks when the level of Lake Washington was lowered by nine feet on the shores of Magnuson Park. The previous creek dried up and Mud Lake shrunk into a small pond. Later the land was changed even more dramatically when the Navy took it over. Nearly the entire area of the park was paved over for runways and Mud Lake was completely filled in and the rest of the topography was leveled out using 1,500,000 cubic yards of soil. It wasn’t until 1981 when one part of the land transferred to the City of Seattle and the rest to NOAA, that it became a park. By that time, only around 30 percent of the park was unpaved. However, it was only turned into a park through the efforts of Warren G. Magnuson, a senator who fought others who wanted to make the space into a county airstrip.

Today the park is the second largest in the city of Seattle with 350 acres and a mile-long stretch of shoreline. The park offers a huge variety of use, the shoreline has a trail for bikers or skaters, there are swimming areas, a kite hill (built with 40,000 tons of demolished runway), ball fields and tennis courts, a community garden, a large off-leash dog park, buildings for events, a backyard wildlife demonstration garden, nature areas, playground, wading pool, public art and most recently, reconstructed wetlands. Many of the old buildings are in desperate need of renovation and one has recently been fully renovated into a large indoor sporting facility. NOAA also has a home on the northern section of the park. The entire park is an opportunity for wildlife with over 100 species of birds seen around the park. There is also a butterfly garden designed by a local school and other habitat throughout the park includes grasslands, shoreline, woodlands and of course wetlands.

The most recent renovation to the park is the new wetland system and sports fields which officially opened in September 2009. With funding from a Pro Parks Levy, the wetlands project was $3 million while the sports fields were just over $9 million. The project removed 10 acres of concrete from the park in just the first phase. Currently two phases are complete with one more addition coming this year. The third phase, called the Shore Ponds project will expand the wetlands to the southeast across the street in an attempt to come closer to connecting the wetlands back to Lake Washington. The construction should be underway with completion at the end of this year.

It wasn’t an easy project though, as the Landscape Architects and Parks & Recreation had to balance the demands, needs, and even a lawsuit between the wetlands and adjacent sports fields. However, the Landscape Architect on the project, Guy Michaelsen, from the local firm Berger Partnership, was able to make the sports fields work for the wetlands and tie them together. The sports fields actually soak in rainwater first, before it moves into the wetlands. The wetlands comprise of a 14-acre network of connected ponds which treats runoff from surrounding parking lots and the sports fields. However, the sports fields and wetlands are connected in more than just runoff, the wetlands wrap around the fields creating a sense of integration. The ponds closest to the fields are more square in shape, illustrating their man-made nature and tying back to the sports fields, but as one moves further into the wetlands the shapes become more organic.

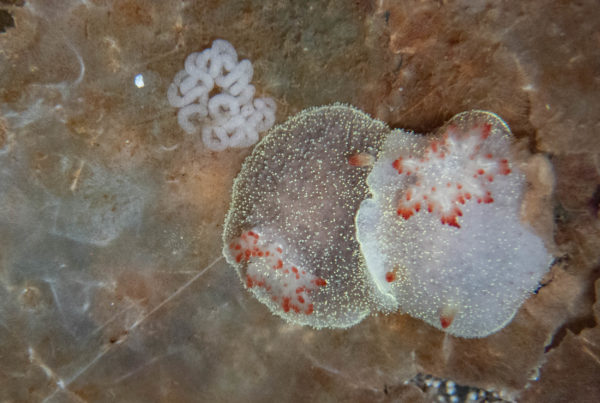

The wetlands are no simple design themselves. They were planned with ecologists and engineers and are very complex, especially with the challenge of such a flat site. Engineered wetland concepts such as leaky berms, log weirs, rice paddies, willow-wattles and sponges were employed to move the water through the system of 63 connected ponds which vary in depth. The material that was excavated for the ponds was in turn piled up into berms and view points creating a brand new topography on the site. The ponds closest to the sports fields are emergent wetlands, shallow and designed to dry up during the summer. During the winter however, they are all connected and act as a rice paddy, one draining into the next. The larger ponds to the east however, are the deeper ponds which retain water year-round. Currently, the water exits the wetlands through a drain pipe into Lake Washington. However, they are designed with the potential of creating a lagoon in the future which would connect directly to Lake Washington. Thousands of native plants were added to the site along with dead wood foraged after wind storms leaving many snags and logs throughout the wetlands. No wildlife species were introduced to the site, what is found there today is the result of the success of the design.

And there is an abundance of wildlife in the wetlands. The Pacific Chorus Frog breed in the park and in fact this is one of the largest populations in the city. Many birds commonly visit, during the summer I saw Cedar Waxwings, Red-wing Blackbirds, California Quail, several species of swallows and hummingbirds and Goldfinches. The winter months bring shorebirds and waterfowl to the ponds. Insects also are abundant around the wetlands and I observed a dozen species of dragonflies and damselflies, countless species of bees, flies and wasps, many butterflies, grasshoppers and beetles everywhere. Leaves were rolled up every step along the paths with larvae, pupae or cocoons inside and lady beetle pupae shells could be found under many leaves.

The wetlands have been a success earning multiple awards. In 2010 the Washington Recreation & Park Association awarded the park’s wetlands and athletic fields project their annual Best Park Design Award. Also in 2010 the wetlands won the EEA (Engineering Excellence Award) National Gold Award for water resources.

Visit the Flickr Gallery for all of the photos

Further Reading

- Warren G. Magnuson Park:: Seattle Parks & Recreation

- Warren G. Magnuson Park – Wetlands and Athletic FIelds Pro Parks Project Information:: Seattle Parks & Recreation

- Nature in the City: Seattle : Walks, Hikes, Wildlife, Natural Wonders

(Book)

- Seattle’s Magnuson Park makeover attracts all kinds of creatures:: Seattle Times

- Ballfields and wetlands: Magnuson Park’s makeover nears completion:: Seattle Times

I was never aware of this project. I have noted in the past that appreciation of nature was a Northwest value. This is one of the best examples of this I have seen. Thanks for the post.