I pass forth into light–I find myself

from ‘The Picture or The Lover’s Resolution ‘ by Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Beneath a weeping birch (most beautiful

Of forest trees, the Lady of the Woods)

The birch tree has firm roots as an important tree in folklore. It’s the first letter of the Celtic ogham alphabet, Beith and in early Celtic belief, the tree symbolized purification and rebirth or renewal. Besoms or brooms made from birch twigs were used to purify homes and gardens and even is the root of the iconic witches broom.

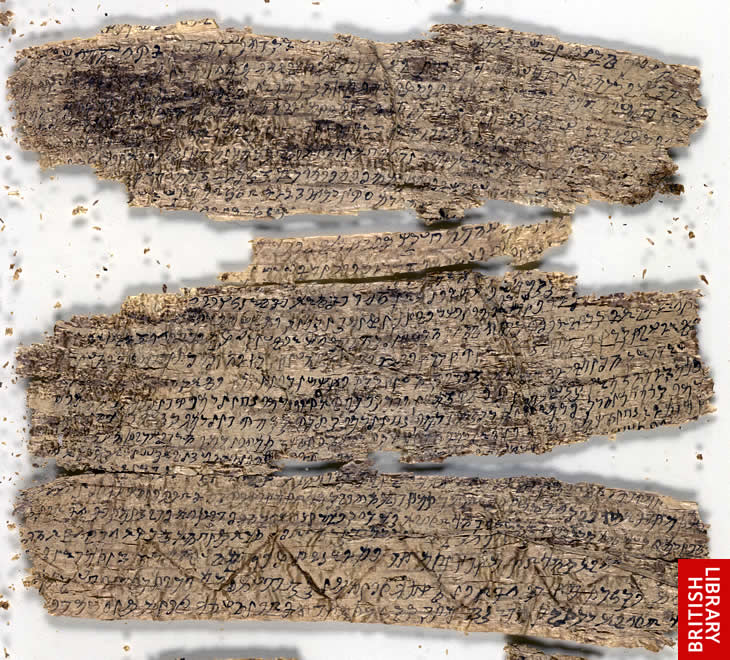

But the tree’s name hints at another use of the birch. The word ‘birch’ is believe to have originated from ‘bhurga’, a Sanskrit word meaning ‘tree whose bark is written upon’. Birch bark writings have been found throughout many cultures, and some are incredibly old. The Gandhāran Buddhist texts are the oldest birch bark writings found and are thought to be from the first century.

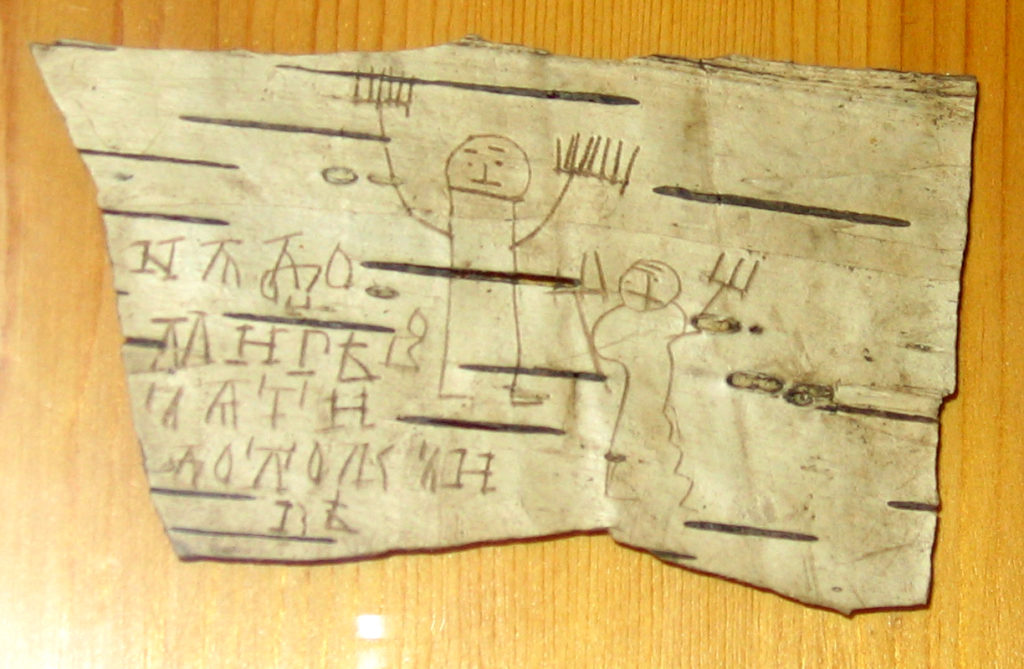

The writings are not written in ink, but instead carved with an instrument, like a stylus, into the bark. There are many different manuscripts and fragments from other cultures around the world as well. Several birch bark letters have been found in Novgorod, originating from the 11th to 15th centuries. Many of the fragments are letters, some very entertaining (“It is my oak. Your former beekeeper has fallen into robbery.”), wills or other communications of business or everyday life.

One particular piece from Novgorod in the mid 13th century contains drawings and lessons by a young boy named Onfim. In another of his pages, he writes himself as St. George in the story of George and the Dragon.

In some regions, birch was a readily available material for writing and could be less expensive than parchment. It’s extraordinary that pieces of birch bark have survived for so long when many of the letters were meant to be ephemeral and thrown away. This was in large part because of the landscape they were preserved, which had waterlogged clay soil. And the fact the letters were carved meant ink could not fade.

Resources:

The Birchbark Documents in Time and Space – Revisited by Jos Schaeken

The Rosetta Stone for Old Rus Was… a Piece of Birch Bark? by Nicholas Kotar

Gandharan Scrolls from the British Library

Birch Bark Letters by Asya Pereltsvaig